Namibia’s strange geography is the legacy of bizarre 19th century colonial politics. A 550km long finger of land (about 30km wide) sticks out of Namibia from its north-eastern corner and pokes out in a straight west to east line through Angola, Botswana and Zambia before its tip reaches Zimbabwe. The tip of the finger at its westernmost point is where the borders of four countries meet on tiny Impalila Island: Namibia, Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The Caprivi Strip, named after Count Leo von Caprivi, the German foreign minister at the time, was ceded to German South West Africa so that it would have an access to the Zambezi river and, from there it was hoped, to German East Africa, through the Portuguese and British colonies which surrounded it. Today, it is a part of Namibia which does not quite fit. After driving past the veterinary barrier north of Grootfontein, and 100km south of Rundu where the Caprivi Strip begins, Namibia sort of stops and traditional Africa begins.

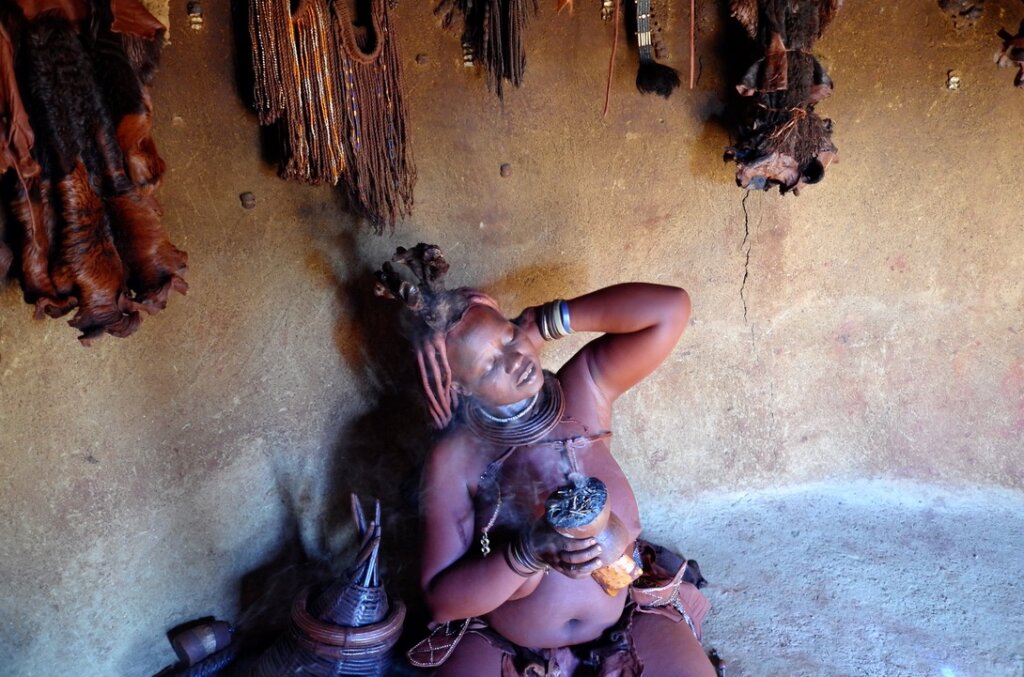

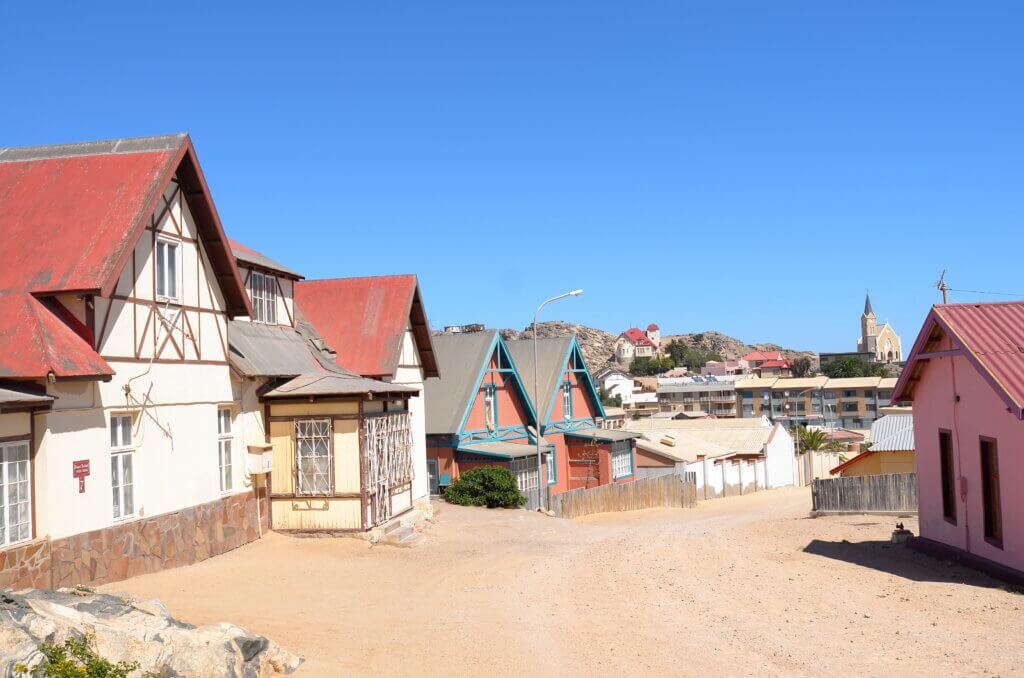

The pretty Cape Dutch and German neo-gothic houses are replaced by villages with traditional huts surrounded by thorn hedges. The large ring-fenced commercial farms give way to communal land with cattle roaming freely on the roads. Heavily laden ladies walk by the roadside carrying firewood or groceries on their heads. The ubiquitous yellow water container which we had not seen for months reappears. And, unlike in the rest of Namibia where all the “rivers” are in effect just dry riverbeds, here the rivers actually have water!

After a stop en route in Divundu on the Caprivi Strip, on 30th April, we drive the last 300km of the strip, travel a further 200km through three countries (Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe) and finally reach Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe, having crossed two borders within a day.

By the time we park our car at Vic Falls, we have driven close to 10,000km through southern Africa, had six tyre punctures, dealt with quite a few (mostly polite and friendly) border officials and had a couple of close cuts on treacherous Namibian roads.