In the last days of our African odyssey, traveling through the pretty countryside of the Free State, getting lost in a hostile downtown Johannesburg , visiting the capital Pretoria and finally a large diamond mine, I am struck by how South Africa encapsulates all that is working – and all that is wrong in Africa. And how it (and the continent) is at a crossroads in its economic and social development.

South Africa’s modern infrastructure is a great enabler to the smooth functioning of its economy. Chinese investment throughout the rest of the continent is in the process of turning potholed gravel roads into a similar network of good roads. But in South Africa, it has also crystalized the segregation between the wealthy (mostly white) who commute to and from leafy suburbs and the poor (mostly black) who live in the run-down city centers where crime is rife.

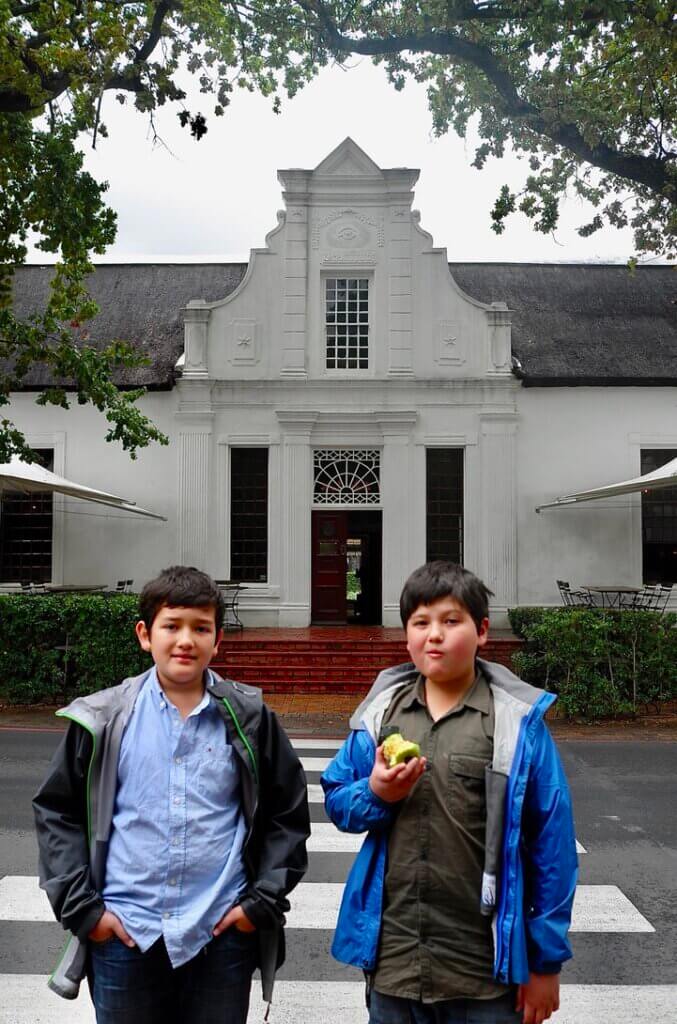

Pretoria is an attractive city, full of parks, grand old colonial buildings and statues of Boer heroes – all of which create a sense of shared history and pride for the white and especially Afrikaner (descendants of Dutch and Huguenot settlers) population of the country. The black majority (90% of the country) cannot identify with these symbols. And apart from the giant statue of Mandela at the Union Buildings, there is little to create that sense of shared history and pride for the majority of the population.

In other African countries too, the government (often heir to the anti-colonial liberation movement) sits in beautiful ex-colonial government buildings designed in imperial neoclassical style. But the national museums which could do much to convey a sense of national pride are crumbling old buildings with infantile exhibits.

The Cullinan mine, outside of Pretoria, produces a quarter of all the exceptional diamonds (400ct and above) in the world. It is a model of social responsibility, investing in safety, in its employees and in the communities around it. Yet, a few years before, it operated (and indirectly supported) the apartheid regime. In neighboring Zimbabwe, like in many African countries, mineral wealth has allowed the kleptocratic dictatorship of president Mugabe to remain in power well beyond its due date.

With Africa’s natural resources now generating more wealth than ever and infrastructure (roads, mobile networks, banking) rapidly expanding this is a unique moment in time for the continent to break out of its poverty trap and create a large, affluent middle class.

This will not happen if African countries can’t create a sense of shared history, values and national pride to overcome tribal politics and rivalries. It will not happen if the majority of the population does not have a stake in that wealth – which requires better education systems and less corrupt governments.

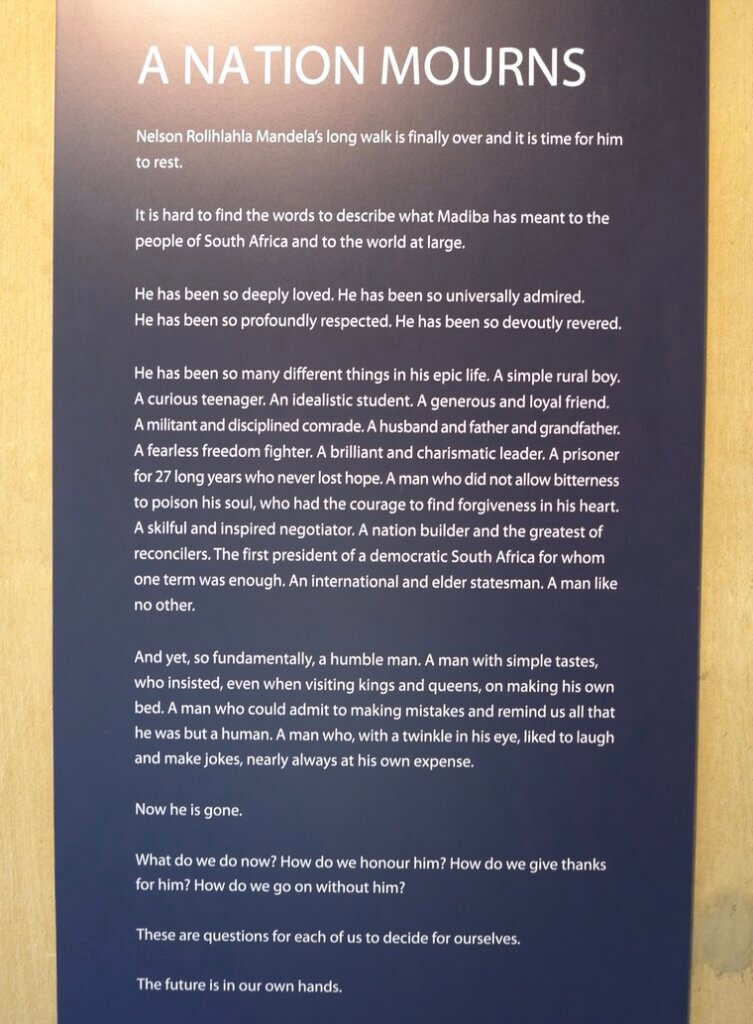

South Africa, 20 years after the end of apartheid, despite all its wealth, is still at the crossroads. Inequality is high (with 42% unemployment), crime continues to rise and the government, now without the moral stewardship of Mandela, is increasingly corrupt. There is a lot the rest of Africa could learn from the SA case study to help it, hopefully, take the right turns on the road to development and prosperity.