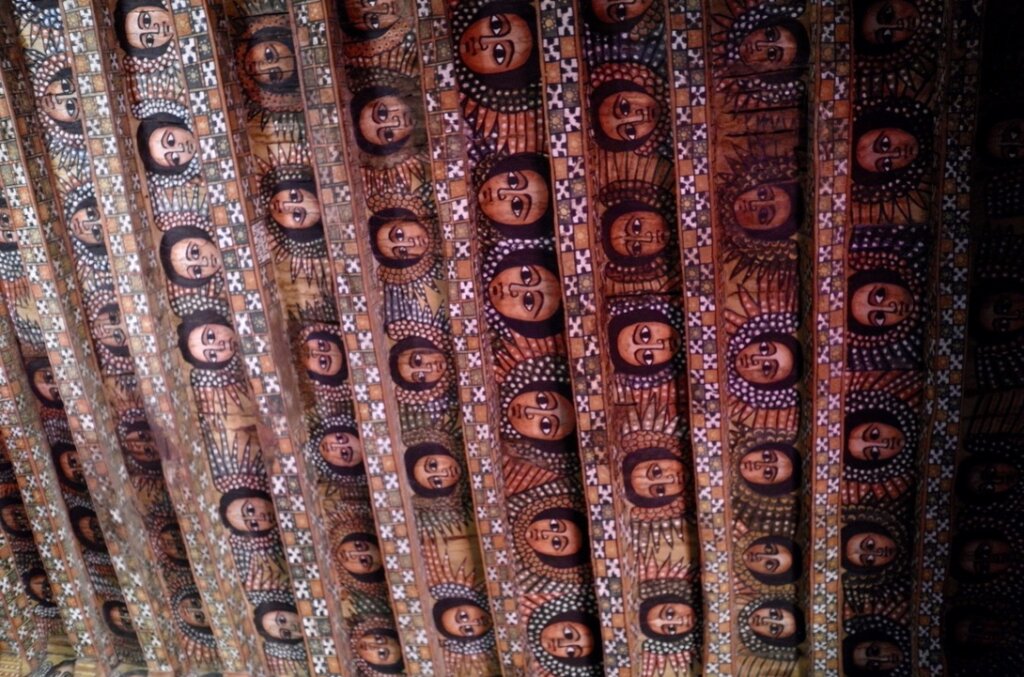

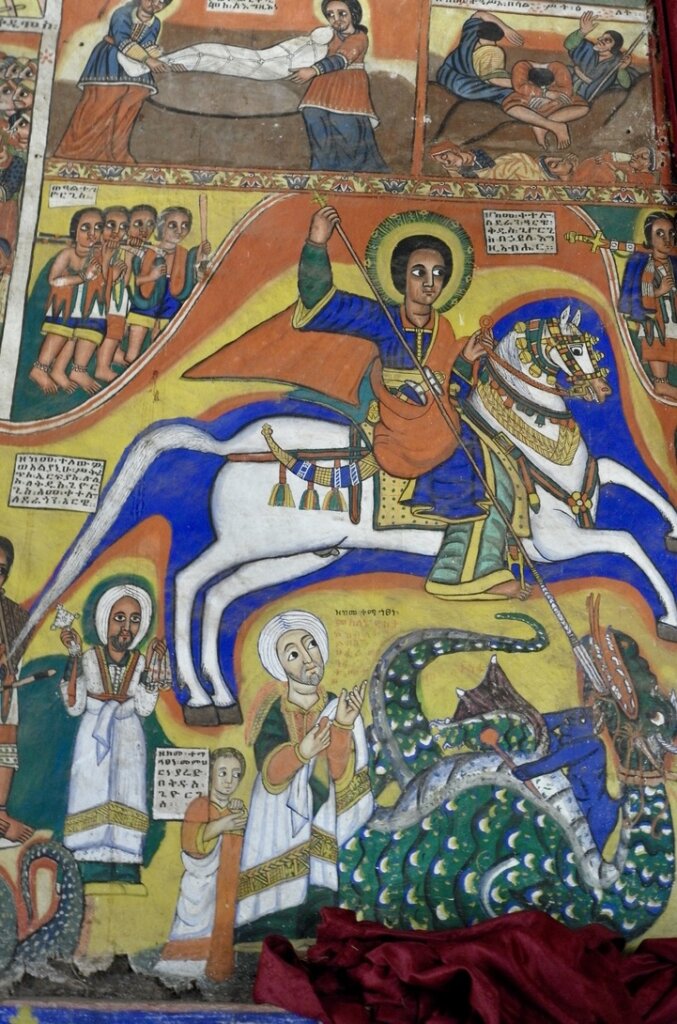

Lalibela, Abyssinia’s capital between the 11th and 13th centuries, is home to the country’s strange and beautiful rock-hewn churches. Carved out of solid rock, the 11 churches built by King Lalibela in the 12th century are wonders of engineering which Ethiopians can’t explain without a divine intervention. Indeed, the king is said to have been transported to the City of God while lying comatose after being poisoned by his brother. There, he was shown models of 11 rock-hewn churches by angels and instructed to built replicas of them on Earth. Angels then assisted him in the construction of the churches, forming a night shift to the day shift of his mortal workers. Even with that divine assistance, it took the king 25 years to complete all 11 churches.

Interestingly, the Lalibela period was a dark age for Abyssinian culture. The arts, literature, science all regressed during that period, despite the building of those spectacular churches which perhaps more than any other monument represent Ethiopia’s rich history.

Our theory to explain that strange paradox is that the Zagwe dynasty which reigned during the Lalibela period and had usurped the throne from the Solomonic dynasty (claiming direct descent from King Solomon of Jerusalem) was eager to legitimize its rule by getting the support of the Church. The Zagwes embarked on that massive program of church construction and simultaneously stifled any form of innovation or creativity in other areas of human endeavor to defer to the Church’s conservative orthodoxy – and gain its respect and support.

A similar situation occurred during the Dark Ages of Europe where only religious architecture thrived while innovation in the arts and sciences was suppressed by the Church.